When everyone believes

Consider the religions of the world - they've been created or evolved at various points in our history and have each shown viral growth to begin with (helped along by concepts like 'colonialism' and 'jihad'), but levels of belief have stabilised. If they hadn't, then the entire population of the world would have one faith, before it's infected by another, to be replaced by a third etc...

Faith itself and political beliefs are not memes, but they are learned from others and are therefore carried by a meme. So it's important to see what happens after saturation has set in, and what causes stabilisation.

Lynch (1998) first demonstrated how memes stabilise by using several pages of calculus, but I think we can simplify it somewhat, and I want to demonstrate it by example. It's a rather old example, but we are still feeling the geopolitical effects of it today.

In March 2004, a year after the US-led invasion of Iraq and (crucially) a few months before a US presidential election, I saw a survey of American voters that showed:

- 57% believed that the Iraqis had been directly involved in the attacks on 11th September 2001 or had been giving 'substantial support' to Al Q'aeda prior to those attacks; and

- 60% believed that Iraq possessed, or had been actively developing, weapons of mass destruction prior to the invasion.

I was, and remain, staggered by this: a little thought would show that the first proposition had never been true and it was by then becoming painfully clear that the second wasn't true either. The survey also showed that voting intentions in the forthcoming election would be strongly linked to beliefs on the rightness of the war, and indeed George W. Bush was re-elected by the narrowest of margins.

These beliefs were clearly transferred memetically - since the facts were not clear, people could not be considering them and reaching decisions independently, and they must instead be inheriting these beliefs from others, but I couldn't understand how these erroneous beliefs reached such high, and stable, levels.

So I retreated to my comfort zone and built a model. It turns out that this model serves to show how competing memes reach stability in a saturated population, and so it is my pleasure to share it with you.

How competing beliefs stabilise

Suppose we have a simple proposition - say, the existence of a dangerous weapon in a certain country - and that every night the population is exposed to some variant of three arguments on the evening news. The arguments are as follows:

- Our leader - a charismatic figure whom you believe is truthful - maintains that the country possesses this weapon and that we are in danger unless we do something about it;

- The man who runs that country, a noted fink, tells you that he doesn't have any weapons;

- An honest and independent (but completely uncharismatic) man tells you that he has been diligently looking for the weapon but can find no trace of it.

Each member of the population can believe one of three things at any given time: either that the weapon exists; or the weapon doesn't exist; or they don't know whether the weapon exists or not.

We will assume that everyone hears the broadcasts each night, and that they make up their minds anew. We will further assume that people are equally 'porous' and so there are no early/late adopter effects, which we won't get to until later.

Now let's assume that, before the first broadcast, 100 people of every 1,000 believe the weapon exists, 200 believe it does not exist and 700 have no opinion as yet. We have limited the population to a thousand, because this makes the explanations easier. By the way, the percentages used here are for illustration only and probably bear no relation to actual views at the time (not that it matters, as we shall see).

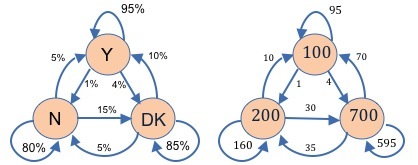

We also know from that a certain percentage of people will change their minds each time they are exposed to the arguments (by the way, the percentages used here are for illustration only and bear no relation to actual views at the time). Let’s say that the defection percentages are:

| Old belief | Now believes ‘Y’ | Now believes ‘N’ | Now not sure (‘DK’) | |

| Yes (Y) | 95% | 5% | 10% | |

| No (N) | 1% | 80% | 5% | |

| Don’t Know (DK) | 4% | 15% | 85% |

The first row says that 95% of people who believe the weapons exist will continue to believe this after the evening news, that 1% of them will be convinced by the counter-argument, and that 4% of them will move to the “Don’t Know” position. Similarly, most people who do not believe in WMD (or who don’t know) will continue to hold that view after each exposure to the evening news. Notice that most people maintain their beliefs and that each row adds up to 100%, meaning that everyone holds one of the three possible beliefs.

So, how does this play out? After the first night, we know that the number of people who continue to believe in WMD is 100 (starting population) x 95% (retention percentage). However, the number of people who now believe that they exist is 200 x 5% from the “No” camp plus 700 x 10% from the “Don’t Know” camp. In short, the total number who believe in the WMD after the first night is 95 + 10 + 70, or 175 - a substantial increase. Similarly, the number of people in the “No” camp is down slightly at 196 and the number of “Don’t Knows” has dropped to 634 as our charismatic leader works his magic.

It might be easier to follow if I use a diagram showing percentages and actual numbers:

The effect of repetition

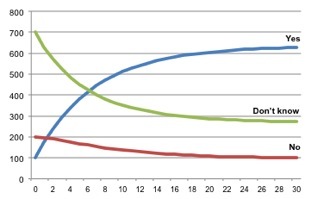

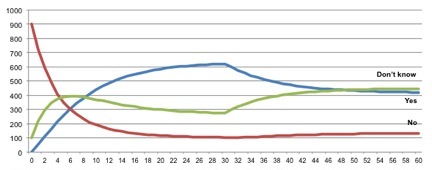

Well, we saw that the broadcasts made some converts on the first night. What happens when we repeat the messages nightly? Our population hear the same arguments, make their minds up anew and moves between the various states of belief according to the defection and retention percentages in the graph and table above. The result after 30 days can be seen in the graph below.

As you can see, after a month, the number of people who believe that the weapon exists has risen from 10% to over 60% and has levelled off, so it's off to war we go.

Although the 'Don't know' belief has a success factor of 1.04, it is smaller than that of the 'Yes' belief (1.10), so the population moves inexorably to the 'Yes' belief. Because there are always defectors to and from 'Yes', equilibrium is reached in the number of people switching beliefs, so the population is never converted entirely to one view.

The irrelevance of history in the face of change

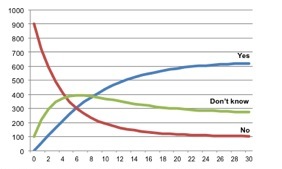

Let us now suppose that the population was initially much more sceptical.

We will stick with the same defection and retention percentages, but let's say that no-one initially believed in the existence of the weapon, 900 definitely didn't believe in it and the remaining 100 weren't sure.

With this starting position, which is radically different from the one above, surely you would expect a different outcome. But when we run the numbers, we get the result shown in the graph below.

Hang on a minute! Although the starting positions are very different and the 'Don't know' camp enjoyed a brief surge, the end result is exactly the same - over 60% end up believing in the weapon. After three weeks, we ended up at the same result despite the dramatically different starting positions.

Why didn't the starting positions make a difference? If you go back and look at the defection percentages, you will see that there is a rapid drift from 'No' to 'Don't know' and from 'Don't know' to 'Yes' against a much slower drift in the opposite direction. That we reach a stable end state is an example of a mathematical phenomenon known as a 'Markov chain equilibrium'

The effect of changing minds

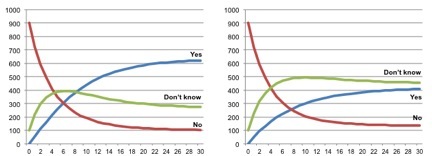

How important are these retention and defection percentages? Let's look at what happens when two people in every hundred are less susceptible to the charisma of our beloved leader and defect to the neutral 'Don't know' camp, and five of every hundred doubters choose to remain undecided for one more day. The defection and retention percentages are now as follows:

Old | beliefNow believes ‘Y’ | Now believes ‘N’ | Now not sure (‘DK’) | |

Yes (Y) | 95% | 93%1% | 4% | |

No (N) | 5% | 80% | 15% | |

Don’t Know (DK) | 10% | 5%5% | 85% |

Pasted Graphic

Pasted Graphic

These differences in defection percentages do not look that radical, but the pair of graphs below show the difference this relatively small change makes to our equilibrium. The effects of the original set of defection percentages are shown on the left and those of the new set are shown on the right.

So even those minor differences in the propensity to change beliefs make a big difference in the end result - the hawks remain in a minority. So we can conclude that a relatively small change in the proportion of people who adopt or defect from a meme can make a huge difference in the final equilibrium, more so than the starting percentages.

Is this all preordained?

Let's try one final experiment: what if the defection percentages change part-way through?

The graph below shows what happens if the percentages in the first table are followed for 30 days, and then something happens to change the public's actions to the percentages in the second table.

Wow! As expected, we end up at the new equilibrium, but look how quickly public opinion shifts! Within 10 days, the doves outnumber the hawks. If you were a supporter of the original proposition, this would be disastrous.

But, I hear you cry, I'm not trying to invade another country - why does this matter to me? It matters because it underlines the need to prevent defection from your ideas in the face of competition, either to other new ideas or back to the old way of doing things.

When trying to design a meme, one of the most important things to remember is that people will defect from it, and that you must minimise the extent of defection. Once a 'war of ideas' has started, the defection percentages will determine who wins it.

Trapping states

We have looked at what happens when memes compete, and how small changes in defection percentages can have a major effect of the population running that meme. But what happens if there are memes that no-one ever defects from?

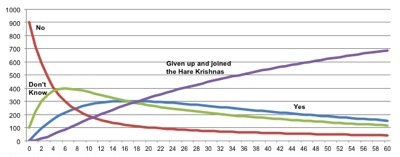

We can test that by adding in another case to our earlier model. Let's say that in the face of all these conflicting and confusing messages, it all gets too much for a small element of our 'Don't know' group - they have a breakdown, throw out their TVs and join the Hare Krishna cult, hereafter denoted as 'HK'.

We'll say that 'HK' is a trapping state (sometimes called an 'absorbing' state), in that no-one who runs this meme ever defects from it, because they no longer hear the competing messages.

Keeping the same starting position, our defection and retention percentages look like this:

| Previous belief | Yes (Y) | No (N) | Don’t Know (DK) | Hare Krishna (HK) |

| Now ‘Y’ | 93% | 5% | 5% | 0% |

| Now ‘N’ | 1% | 80% | 5% | 0% |

| Now ‘DK’ | 6% | 15% | 85% | 0% |

| Now ‘HK’ | 0% | 0% | 5% | 100% |

| Starting position | 0 | 900 | 100 | 0 |

Pasted Graphic 1

Well, this is what the result looks like:

After nine months or so, all but a handful of people have fallen into the trapping state.

Summary

Memes spread by imitation and are transmit concepts (consciously or otherwise) through a population. In a 'virgin' population, the meme spreads at a rate of change equal to the current population multiplied by the success factor.

If the success factor is greater than one, as it was with our zombies, then we see exponential growth. If it is equal to one, then the population remains level and if it is less than one, then we see a decline in the infected population. The success factor is a constant, ignoring saturation and defection.

The most important factor affecting the total population is the reproduction rate (i.e. the time between generations). The next most important is the number of copies per generation, and the least important is the number you start with. When we look at marketing, we will see that mass advertising needs to exist because adverts are not good memes.

We also saw how saturation of memes in a population causes the rate of increase to slow down, meaning that the success factor drops, and that once we are starting to reach saturation - as we are in most real-world cases - we have to start to model defection between memes.

Simple models called Markov chains can be used to model meme growth, and we can see that:

- if defection rates are stable, then the end state depends entirely on the defection rate and not at all on the initial state;

- a relatively small change in the proportion of people who defect can make a huge difference in the final equilibrium;

- if there is a 'trapping belief', most people will eventually hold it, which goes a long way to explaining the ubiquity of religion in many societies throughout history;

- if you want the population to retain your beliefs, bundle in an immune system to prevent them from defecting.

Here's one final thought: if you are working in an industry where competition is fierce (i.e. saturation is complete) and customer loyalty is low, why are you spending your time chasing after everyone else's customers? You would end up with a much greater market share just by stopping customers from defecting once you've got them. This is a theme we will return to in an article on selling in saturated markets.