Sneezers, connectors and castrated sheep

Many of you interested in marketing will have read Malcolm Gladwell’s wildly successful 2002 book, The Tipping Point. To condense his argument somewhat, Gladwell says that there is a point at which an idea or a product really takes off, and that this phenomenon is driven by three types of people:

- ‘connectors’, individuals who have links to many different worlds and transfer ideas between them;

- ‘mavens’, who have a strong compulsion to help others to make informed decisions; and

- ‘salesmen’, who, well, you can guess what they do.

In Gladwell’s world, the spread of a new product or service is determined by the initial adoption patterns of a small group of ‘socially infectious’ early adopters. Through recommendation and imitation, these ‘connectors’ drive the spread of the product in a wider population, resulting in exponential growth.

Seth Godin comes up with a very similar concept in his 2002 book Unleashing the Ideavirus, where he says some people, who he calls sneezers, are naturally more inclined to pass on ideas to their friends. People will tend to listen to those they respect and admire, and so the sneezer gains from the transmission of good ideas as well as the sneezee. Similarly, both lose from the transmission of dumb or irrelevant ideas (so those celebrities you see pitching products on TV are trading their credibility for money). If you can build up a core of evangelizers among these sneezers, Godin says, your idea is much more likely to spread.

Gladwell and Godin urged marketing men and women to seek these connectors out and influence them, rather than going for the whole population, and marketing men and women took to this simplifying idea in droves. Klein (in No Logo) identifies a particular obsession with connectors in the youth market.

If you’ve taken part in a market research survey recently, you will have noticed questions like ‘are you always one of the first people to get the newest mobile phone?’ or ‘do people tend to ask your advice about mobile phones?’ If you answer yes to either of these questions you'll never get the marketing people off your back.

The Bellwether

This is not a new idea: for as long as man has been farming, we have known of the existence of ‘connector’ sheep called bellwethers.

There are certain rams that the flock naturally imitates: if this particular ram wanders over to one side of the pasture, the others follow. If the ram bleats, the others will too. When they notice this, the shepherds and farmers grab the ram and tie a bell around its neck. The poor critter is castrated (a wether is a neutered ram) to make it easier to handle, and belled so they can identify it. The shepherd’s life is now a whole lot easier: rather than herding fifty sheep, they just have to herd one and the rest will follow. The castration and the bell don’t turn the sheep into a connector, they are just the unfortunate end result of being a style icon.

Sheep have mental models that revolve around grazing, predators and occasionally sex, and I doubt if there is that much difference between the cortical pathways in individual sheep. But humans are much more diverse and this is where I think the ‘connector/sneezer’ theory falls down. Sure, Gladwell’s connectors have ethos, the mavens represent logos and the salesmen generally use pathos, but the very thing that makes the connectors so valuable, their willingness to try cool new things, undoes their usefulness.

Let me explain….

Change the memes, cross the chasm

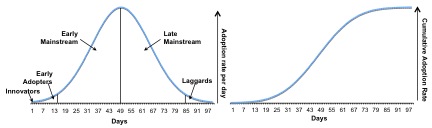

Back in 1962 Everett Rogers told us that the rate at which people adopt an idea falls on a bell curve. About 2.5% are innovators, 13.5% early adopters, 68% mainstream and 16% are laggards like me.

This is how the maths works out: if we assume that it takes 100 days for an idea to spread throughout a population, then the rate at which people take up the idea looks like the left hand side of the picture below. By the end of the first 30 days, you may only have got the message out to 10% of the population. After another 30 days, you’ve converted about two-thirds of the population, 90% after 70 days and after 80 days you’ve got pretty much everyone. When plotted as a cumulative distribution, you get a ‘S’-shaped adoption curve, like the picture on the right, and you will recognise as the S-shaped saturation curve we saw earlier.

This is where the notion of the ‘tipping point’ comes from: it is the point on the cumulative distribution curve at which sales straighten out and continue to rise, in other words the maximum gradient. As this only applies in unsaturated markets, higher success factors for the underlying memes lead to lead to narrower distribution curves and therefore more pronounced ‘tipping points’.

Why tipping points don’t matter

Tipping points undoubtedly exist, and the bellwether phenomenon is real (at least, in sheep), but I still struggle with Gladwell’s and Godin’s ideas because many successful niche ideas do not spread into the mainstream. The films of Ken Loach, David Cronenberg and Woody Allen are wonderfully made, receive rave critical reviews and are popular with the art house crowd, but Joe Public queues up to see Police Academy 38 instead.

And the proportion of people who wear designer clothes instead of Marks & Spencer or JC Penney is tiny, not just because designer clothes are stupidly expensive but because they are often just plain stupid. The Segway and the Apple Newton, despite being amazingly cool, failed to achieve lift-off. But surely if the connector/sneezer theory is right, these products should dominate their industries?

The answer is fairly obvious when you think about it - different segments of the bell curve see things differently. Geoffery Moore explained why many fashions fail to take off in his 1991 book, Crossing the Chasm. The answer is that innovators and early adopters are not just more porous to new ideas, they don’t think in the same way as the mainstream. There is a chasm between the two groups, and it’s one that many products fail to cross.

The innovators and early adopters are visionaries that tend to buy things because they like them, regardless of quality or cost. The place a high value on uniqueness and ‘cool’.

The mainstream are pragmatists who value old-fashioned things like predictability and price and are much less interested in how it makes them look. The mainstream market isn’t going to hack the iPhone to make it work on their network or so they can install a new app: if it doesn’t already work every time, they won’t buy it. And they certainly aren’t going to spend $1000 on a badly-made pair of jeans because they have a pretty label.

One valid reason for starting with market innovators is that they are more tolerant of minor faults. As we will see in the article on the growth of the personal computer, marketing straight to the mainstream is disastrous if the product is not completely bug-free: while innovators see bugs as a challenge, pragmatists see them as a showstopper

The doctrine of the social connector says that winning them over will inevitably lead to mainstream sales. But early adopters will be attracted by what are essentially fashion memes, and the other 87% of the population are not, at least not to the same extent.

Different underlying values imply different selection pressures, and if you aim your products at the innovator niche, that’s all you will ever conquer.